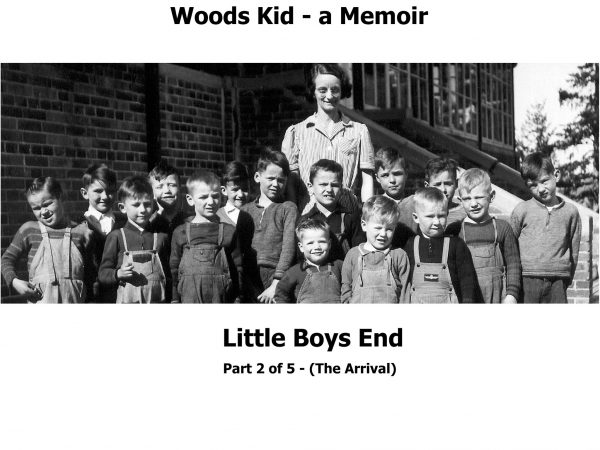

Pictured above, little boys outside their dormitory – once a solarium on the north side of the Hextall mansion house. The year is 1947. The author, Frankie Dwyer , is in the front row, on the right, in overalls and black top. Our matron, Miss Ethel McArthur stands in the rear. Copyright the Glenbow Archives (see photo credits at end of material on “Welcome to the Home” page.)

Caution: Readers should be aware that in this account there are occasional graphic descriptions of violence and abuse that may be unsettling for some. My recollections are unvarnished. I do not shirk from describing abuse of children. With what we know, including national inquiries in the U.K., in Australian and now New Zealand these things are sadly commonplace. It is unlikely the Wood’s Christian Home would be different, and in my experience it was not.

I came to the home on November 4, 1946. (We arrived on the little, wobbly trolley car that ran on rail tracks.)I was four years old, only a month from being five. My mother had disappeared when I was ten months. She and my father had connected in Vancouver as a wartime liaison, one of many in those dark, early war days. They travelled to Toronto from Vancouver, where my dad went to work in war-time factories. He had been rejected for service in the army, since he was blind in his right eye and had a deformed right foot, both from childhood farm accidents. He helped assemble Mosquito fighter bombers for much of the war. Why my mother left is not known, but in a near miracle – some seventy-five years later I learned about her life. In effect, discovered her and her fate. (Mostly through the efforts of a fellow old boy, J. Richard Nickel of Gympie, Queensland, Australia. I am forever grateful to Dick.) When the war ended, my father and I took the train to Calgary. His life there was rough, so it wasn’t long before he might have been urged by the police to put me into some kind of care. That is how I came to the Woods.

We woke to a clanging hand bell wielded with excessive enthusiasm by an older girl. She would appear at seven to shatter our slumber. She then bolted for the outer door, dashed across the cement slab and did the same at the multi-story big boy’s dormitories.

The result was pandemonium. Eighteen small boys bolted from beds, pulled on knit slippers, and hurtled across the formal oak room. With a flurry of elbowing, they tumbled down broad stairs to the dungeon-like boy’s toilet. There was a left turn on the lower landing, and being slick, polished hardwood, invariably several would lose footing and crash into the end wall. Sometimes shoves ensured that inglorious pileup.

In the decade following my arrival in 1946, typically around a hundred children lived at the home. The staff consisted of a matron, a boy’s supervisor, a little boy’s supervisor who also managed most of the girls and a full-time cook. There was a laundress too. I remember them as ample and mostly cheerful ladies. The matron and supervisors lived in. They had one day a week off.

The matron when I arrived was Mother Blackadar, an elderly woman, who had worked with the co-founder, Mother (Annie) Wood, who had died years before. Miss M, in charge of little boys, was a fixture at the Home. A spinster, she often wore a striped cotton dress, belted. M had severely parted, black-dyed, hair. The wire-rimmed spectacles stood out. Why I choose to call her, only by the moniker M will become clear to readers as I relate my memories. She is dead now; they are all, with the exception of a special teacher; the most loved of all our guardians. There will be more about her, and the other remarkable teachers, in subsequent parts of my memoir.

The one who died first had an impact on me, as I carried out one of the little boy’s duties. That was mother Blackadar. I had the assignment of carrying her silver breakfast tray into her bedroom. I did not know that she was dead, just slumbering I thought, her grey hair luminous in the soft light. I knew later by the wailing and the tear-flooded eyes. All my life I remember crowding into the main dining room with older kids. The dark outside, and the brilliant lights, with the wonderfully sweet children’s voices singing Abide with Me, some soprano girl’s voices soaring, their faces tilted and their cheeks glistening with tears.

The small boys slept in what had been the solarium, the sunroom, of a former tuberculosis sanatorium operated, for a few years, by a religious order in the 1920s. We called our dormitory the little boy’s end. An eccentric British born property developer, John Hextall, built the great house in the early 1900s on the western edge of Bowness, as a showcase residence. By 1946, it had become a home for orphan and disadvantaged children. The place was an immense and fading Tudor style mansion house. The main floor was finished with hardwoods. The formal Oak Room, which adjoined the boy’s sleeping quarters, was exquisite, spooky at night. It’s no wonder we had bedwetters. Having to cross those shadows and descend into the basement after dark would have deterred all but the bravest. They later placed a pee bucket at the entrance. Certainly, a kind, if odoriferous, improvement. If it had been me who had the task of carrying it down to empty every morning, I would have feared slipping on the waxed, hardwood stairs.

There is some irony in this, the mansion-like furnishings since we were poor. Some, a minority of the children were wards of the province. For their care, the Home received one dollar a day. A parent or relatives had put most others, like me, in independently. Those handing us over committed to pay thirty dollars a month. From this sum, a dollar was set aside, converted into dimes, and put into a small tin box; the tins arrayed temptingly on a shelf in the manager’s office. I say temptingly, not because someone might steal from them. There were no thieves in the home. The culture would not abide that but tempting because we could hardly wait for Saturday mornings. We would line up and the manager, Mr. Robertson, the very picture of a businessman, reached into the tins and handed a dime to each outstretched palm. We were free, then to go to the store and spend all of it. A dime then would buy, splendidly, thirty jawbreaker candies. Six cents would buy a cola, but we would not waste money on something as transitory or fizzy as a soft drink. We could suck on jawbreakers, with multi-colored layers, for it seemed ages.

I was one of the youngest. There were two others about my age, brothers, who were to become my best friends, whom for the purposes of these recollections I will call Scooter and Cheeky – well, we all had nicknames. Unlike me, they were wards of the province. They had come in before my arrival. There was certainly one difference. I am sure that their parent did not get the same information as mine. My dad, as were all parents at the time – most single parents – were told that they could not visit their child for one month. Visits took place on Saturday afternoons and for an hour or so after dinner, depending on the child’s age. Weekend visits away from the Home with parent or relatives could not happen for some months. That was policy intended to break the bond between child and parent. It helped to ensure we became Wood’s kids. One mother, whom I knew well in my later adult life, told me that her boys inquired why she did not visit and were told by the boy’s supervisor Mr. T (to be consistent) that the Home did not know why she did not visit.

The small boy’s rooms in the basement had an outer space, a boot/change room, where there was a row of lockers. We kept outerwear there. This adjoined the playroom, which was a concrete box. The only furnishing a large, and sturdy, wooden table – more of a platform. This platform often became the castle. The idea of the castle was that a dominant boy would hold it, standing on top, often with lieutenants, whose role was to repel the rest of us who tried to gain the castle heights and depose the king. Violent chaos ensued. This might have prepared us for life in the big boy’s dorm. That and the exuberant game of murder ball that we watched on the vast front lawn. The older boys lined up, half-way down, spanning the field. One unfortunate was then selected to carry the ball and try to run through the howling line. Of course, no ball carrier eve succeeded; the idea being a great pile on.

The washroom was on the right off the playroom, with a row of sinks and toilet stalls. The toilet cubicles lacked doors, which was consistent with practice in the home. It might have been to save doors and hinges from damage, but the reason cited at least as far as the bigger boys was to discourage undesirable habits. Little boys had no idea what that meant.

The dominant fixture was the bathtub. The tub, a large one, sat elevated on a wooden platform that had slats. Two boys bathed at a time. Older girls bathed on Saturday night, making liberal use of hard bristle scrub brushes on our knees and elbows. Bath night saw us all naked in the steam-filled room, engaged in exuberant play, tossing water and sliding on our butts across the flooded floor. It was all a chaos of shouting and splashing.

After bathing, we lined up, dressed in housecoats, and knit slippers, for inspection. Miss M, the severe and dominant little boy’s matron, inspected. We thrust our elbows up for her examination and had our ear lobes pulled, while she peered into ear canals. We then thundered up stairs. The big girls, who had bathed us, must have drained the flooded floor, and gone off to change their sodden dresses, hoping for a dryer assignment on the next roster.

Bedtime was seven PM, no exceptions. We slept in single, white-metal cots. The blanket was a wool, grey army sort (which would soon feature in a disastrous experience for me). In winter, we got an additional blanket. That blessing vital, because the sunroom (former mansion solarium) we slept in had long and narrow, continuous windows all along the outside walls, with no drapery. There were steam radiators, too few, which thumped and hissed and did little else. We slept tightly curled in fetal positions.

No talking was the rule after lights out. We whispered. Sometimes, Miss M would creep in and snatch a misbehaving boy. One time, she even crawled part way in, under the beds, to burst up and grab a talker. Boys seized in this way, went somewhere, I did not know what happened to them, but I soon found out. The behaviour of many of the small boys was always taunting, daring. We giggled and jumped on our beds with abandon. That was true for most of us. We were stubbornly happy, defiant, and mad about play. It would be no falsehood to say that we were a band of little, happy brothers. Then, we were sheltered and were not yet aware that we would eventually go up to the big boy’s dorm.

We took our meals in a special little dining room. There was a long, oilcloth-covered table with benches. We crowded in. They allowed talking, at least a small amount. That differed from the main dining room where the rest ate. Talking though could still get you into trouble. Miss M took to calling me gabby. Soon I had to sit with my back to the big windows so that events outside would not provoke my inquiries. On one occasion, I exasperated our keeper, and she dragged me out by my ear, for lockup in the main hall closet for an hour or so. That is where, I learned, she sent misbehaving boys for correction. Miss M believed in isolation, darkness, (even if provoking irrational fears), as the correct remedy for misbehaving boys.

I learned to make beds. From your first day, you made your bed with hospital corners and tight blankets. My bed was my refuge, but for some boys the bed was a mixed – even occasionally terrifying thing. The few boys who wet the bed regularly had reason for terror. You knew by the smell as soon as you woke that someone was in for it. The offender, and they were chronic repeats, would have his nose rubbed on the sodden sheets and be forced to bundle his sheets up and take them to the laundry room. This, ordeal enough, was nothing to what would await them when they eventually moved in with the bigger boys.

Cheeky was a bed wetter. He was mentally challenged and odd looking. Cheeky had course features, dry looking hair and a protruding belly. His brother and he were both short, almost midgets. They became my best friends. Some of the luckier boys could get hold of comic books. I remember sitting against the playroom wall on the concrete floor – there were no chairs or benches, reading comics with Scooter on one side, Cheeky on the other and a crowd of boys pressed against us. I learned to read early. I do not know how, precocious in that way. It served as a kind of protection for me. Decades later, I met up with Scooter, and I asked him, “Why didn’t they beat me up regular like they did your brother?” He replied, “Because they thought you was a genius, being you read books and stuff.”

I started preschool when I was five. (The same age that I got my first weekly chores assignment, to polish the landing below the oak room stairs.) All of us, excepting high school grades, went to school in a large room, also down in the basement. This likely had been a ballroom in the former mansion. The small number of kids for high school went out to schools in the adjacent Bowness community. I recall that there was a mezzanine where you walked into the room. There were maybe four of us in playschool there. The once grand dance floor was school for nine grades. On Sundays, they transformed it into a church. A fire and brimstone type of preacher, Baptist I believe, would lead us in stirring song. We sang, “Jesus Loves the Little Children, Rock of Ages and, for military minded boys, “Onward Christian Soldiers.”

We stamped our feet in a great imitation of marching. Some of the old boys inserted profane words into verses, which caused sniggering. Before service, all of us in Sunday best (which was ragtag) received a penny for collection. The peculiar collection bowl happened to be hard plastic replica of a pirate’s pot of gold. It had a slot in the top, centred in the replica pile of Spanish gold coin; and a large screwed in plug at the bottom for later extracting the horde of pennies. The drill was, and we all knew it came down from the boss boy, was that as they solemnly passed the bowl along, the recipient would lift eyes skyward in reverent manner, drop the copper in and with a hidden hand give the plug a little turn. This ensured that at some point in its travels, the plug would release and a cascade of coins would tumble over an unwitting boy’s lap and careen noisily all around. I can still remember the impulse to clamp a boot over a stray penny, thus keeping it hidden for later retrieval. That bounty could fetch three jawbreakers or maybe, less desirable, a few slices of bread.

When church let out, we were set loose. In the summer we played, on weekends, at a weedy, but large playground across from the Home’s entrance gate. There were all the usual playground amenities of the time, and scant attention to safety. Bigger boys sometimes took the swings over the top and might be seen nonchalantly perched atop the highest pipes, with a leg dangling casually over each side. Small boys played in the general melee. Sometimes older girls took an interest in us, and one such led me into a disaster. She had no such intention of course, when she taught me how to knit yarn with a spool knitter. What happened as a result, strangely and awfully, affected me for a long while and maybe it helped to shape my character – being I hate injustice.

Kids made the spool knitter from a large, empty wooden sewing spool. Four finishing nails were driven, equidistant, into the top to leave about one quarter inch protruding. The knitter pulls up the yarn and casts on by looping around the nails. The result gradually piles up into a woven strand of yarn that trails from the bottom. This, oddly, fascinated me. I was only five years old, but I could do it and it happily provided me something to occupy myself in bed before sleep. In the little boys end we went to bed at seven, and it might be an hour or more before we mostly nodded off. I wove happily in my bed until the inevitable occurred. I ran out of yarn.

I then discovered that there was loose yarn on the top of my grey blanket, so I began, obliviously, to weave away with that strand. Then, one calamitous morning, with two inches of my blanket gone towards my knitting project, she discovered my resourcefulness. The irate Miss M. made me stand in the hallway corner just outside the Oak room for the entire night. I cannot remember now if I sat or slumped, but I endured, though it was in complete terror of what might be stalking out there, creeping along the shadows in the night hallways. What I am sure is that I would not have seen this as a premonition. I could not have known that I would be deliberately venturing out there in only a year or so, also at night, and with a different terror driving me.

Meantime, we had the glory of Christmas. Calgary civic groups would outdo themselves to put on Christmas parties for us. I remember one year when we had five, or maybe it was six. There was a gaily decorated tree outside the little boy’s dorm. They decorated it wonderfully. On Christmas morning, we would rush out, all of us small boys in house coats and there would be piles of gifts. I vividly recall one year getting a Japanese orange, three pieces of ribbon candy, a snakes and ladders game, two Brazil nuts and a real gyroscope that spun sensationally across the oak room floor. It must have been something because I remember all of that from seventy years ago. I also remember, and still appreciate, the Calgary social clubs, the good people in the city and the Home itself for the grand outings we went to several times a year. Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs thrilled us beyond imagination and to see the World yo yo champion! There was an annual sponsored picnic in Bowness Park, where how many hot dogs you could scarf was a badge of boyhood honour. (Does anyone remember the little/flat wooden spoon that came with Dixie Cups, or eating wieners on a string with hands behind the back)? The sack race still merits title of my annual humiliation, but more on my athletic ineptitude later.

Other things happened to me in that final year as a little boy. I must have been six years. I had weekends away, twice with Calgary families. Kind families would sometimes take boys and girls for a weekend experience. The first was marvelous, the second not. On the second occasion, this man, who was as I recall a businessman, had I believe some regular association with the Woods – a volunteer maybe. The guy who came out and showed us movies on Saturday mornings. What happened with him is that I woke up during the night with him fondling me to no effect. I objected, pulling away and he let me be. Not so for Scooter though, as he later said, still surprised at what was a huge amount those days, “he gave me six dollar.” It was maybe three months later when the word went around that they found him out, and he hanged himself in his garage.

My education and preparation for life in the big boy’s dorm was not yet complete. Something else extraordinary happened that year, and in the spring, while I apprenticed as a kitchen thief. We had a chicken coop out in the middle of the backyard. This supplied eggs for the staff room breakfast table. The eggs were not for us. We got eggs twice a year, at Christmas and Easter, a big event. Those eggs must have come in from a supplier. On this particular day, I was playing idly by the chicken coop, when I saw a group of big boys exit the Scout house and head up the hill into one of the forest trails. The odd thing is that they were dragging someone along with a rope. He had a blanket draped over him, tied at the waist. Then there was silence, until I heard wailing sounds up there in the woods. Turns out, he was a so-called faggot boy, and what they had done was whip him. Tied him up to a tree and used a homemade cat-o-nine tails. That boy left, and we never heard anything more about him.

The other thing, and that also haunting, though in different ways, happened over my last summer as a small boy. A new older boy had arrived. He was striking, a wild boy. I remember he had dark, spiky hair and the older boys did not seem to like him much. He was though friendly to small boys, to Scooter, his brother and me. We often played with small metal cars in the silt, the clay bank, behind the big boy’s dorm. He captured a hawk and made a cage there to keep it. It was salvaged wood slats and chicken wire. One day, we found the cage shattered and the bird dead in the clay dust: its beak horribly open and with feathers scattered everywhere.

Not long after this, they found that boy terribly injured in the basement of the big boys’ dorm building. My dim memory is that I had a role in finding him, broken and moaning. Little boys occasionally used the big boys’ toilets during day times. He had somehow got himself under a bench on the lower floor playroom of the big boys’ dorm building. The thing has haunted me for something like seventy years. They took him away in an ambulance. The story that circulated afterwards, was that he had been crushed after a log rolling over him at construction work, up towards the nearby Bowness Golf and Country Club. There was some clearing going on for the new trans-Canada highway being built then, maybe a kilometer away. I remember being awestruck at an ambulance arriving. I recall the jostling and whispering of boys outside the dorm as they loaded him. Of course, as a small boy, I would not have wondered about much else. It has though occurred to me, as I ruminate back on the misty past: how, so horribly injured, did he ever get back all that way from the golf course, up the stairs to the dorm, then down into the basement and wound up under a bench along the north wall? Well, we are never likely to know, as he never came back.

Postscript 25 February 2019. I have spent years trying to learn more about the broken boy – to no avail. The others who might remember are now old or gone. All I know is that something awful happened, way back then, up in the woods above the Woods. I am left haunted. As I put it in Passing Innocence, “Sometimes fragments surface, quite vividly, and visit with me in the small hours of the night.”

NOTE: to continue reading the next chapter, “Lower Boy’s Dorm” click on the MENU at the side of this page. Link to chapter 3 is in the dropdown list. Also, there is a menu on the very bottom of the pages.