We had rules, which was something one became more aware of when moving up to the upper boys. Nobody wrote down the social laws, but the boys knew and enforced them. That is the way it was in barracks life. Paradoxically, the upper dorm turned out to be a safer place for me. I had learned to survive in that kind of “Lord of the Flies” world. That was not true for the few boys who wet the bed or were vulnerable in other respects. The awful thing was that their ordeals came out of a commendable ideal, that of keeping the family together. There were some in there, those we now call challenged kids, but usually only as part of a family unit. They had siblings. Some stayed for years, and the boys regularly savaged them. It is true that a number had protection from streetwise or tough older brothers and sisters. Cheeky did not have that. Miss M had protected him as a little boy, but she had little influence in the affairs of the big boys.

Some of the rules concerned weapons. Making weapons was a constant preoccupation. Only rarely did our inventions cause severe injury. I do not remember zip guns, but we manufactured arrow guns and crossbows. In the spring, we had a mania for making slingshots. For the slingshot’s pocket, the rule said that you could take leather from another boy’s shoe, but only from the tongue. In that way, a kid victimized for the arsenal could still wear his shoes. We also outlawed ball bearings for slingshot wars. You could use stones only. This was not some impulse favoring naturally sourced ammunition, but only that we considered ball bearings, which came from dump salvage, too lethal by far. My friend, Toebuster, who lost two front teeth in a slingshot war, might have disagreed with that presumption. For the occasional but epic slingshot war, boys often dressed in improvised combat garb – old pots and helmets, bulky padded coats, our army cadet greatcoats as they crouched behind improvised barricades. The concept of fast and mobile strike forces had little favour. We went for siege and stone showers. Those campaigns were more impressive than deadly. It was a sniper though, who altered my friends grin. He had the two front teeth knocked out with one shot. I remember the hot contention that the projectile might have been a marble. I wasn’t involved. After my experiences in the lower boy’s dorm, I had lost all desire to become a warrior.

I must not leave the impression that warfare or violence was a constant. More often, we got along. Boys, and girls too, I’m sure. There must have been lifelong friendships formed. All the normal things of childhood played out, including friendships, romances, and enthusiasm. Play was often wildly exuberant. So was risk taking. One boy, the original spider man perhaps, managed to escape from the supervisor’s third story bathroom. (He had been locked in there as punishment.) This, no doubt skinny, lad somehow manage to get out the window to lower himself, hand-over-hand, down the skinny, steel drainpipe that ran from the roof, breathtakingly, some forty or more feet above the unforgiving ground.

I moved up a few years after the new school opened in 1950. That modern building was something like a palace dropped into a ghetto. It had that kind of impact, the place was too much to absorb. There was a gymnasium (scene of agonies for me later), shower rooms, and three separate classrooms. The older kids could go to school on the home grounds and the three teachers could concentrate on the grades nearest to each other. Miss Edmondson taught the little ones. She was tall, gaunt and kind. Miss Farrell had been at the Home for some years. She taught the middle grades and was the one loved most of all by the kids, especially by the girls. Miss Farrell, a sort of Queen of Crepe Paper, organized all the concerts. She put on marvelous, inventive productions that made some of us stars for a time. She was musical too. When we went to school, we found a mostly warm and gentle world, a kind of refuge, which could only be a comfort to most of us. I loved it. If I am anything today, I put it down to the influence and example of our teachers.

The principal and my teacher in the upper class – grades 7 through nine – was Linton Gaetz. Mr. Gaetz (he was always that) was a bit of an authority figure in a kind of reluctant way. He was distinguished looking, often with a bow tie and suspenders, and he cared about us all. It might have been the stress of the responsibility, but he could be surprising. On one of my report cards, he wrote, “Frankie occasionally helps grade nine with a problem (I was in grade seven) and then, in the next term commanded, “Clean up the back of this report card boy (smudges). On one dark occasion, he strapped the entire school. (I cannot imagine what awful offence would have provoked such a draconian response). In that era every teacher had a government-approved strap handy. It came down to him being principal of course, but it must have been an agony and might have triggered a heart attack – he was getting on in years. I remember some ninety or so of us lined up around the gym. He gave everyone two firm smacks on their hands. By the time I faced him, he was disheveled, an exasperated wreck, shirttails flapped out around the suspenders and his face, red and exhausted. On my last report card, he wrote, “Reach for the stars boy.” I loved the man. Many decades later, I attended my first reunion and saw him wheeled in, shrunken, not knowing any of us. Not aware of the assembly of men and woman who likely owed to him and to the two splendid teachers he directed.

Summers were the worst time in the home, except for the wonderful Camp Kiwanis to which many of us went to for a week or so. There was no school. Many children went off to relatives, to farms or simply left for new circumstances. There might have been thirty or so of us left. It being too hot, too far to the scorched playground, we spent the endless days in the shade of the great house, playing marbles or jacks and emulating the girls, at hopscotch. Yes, smaller boys played girls games in the dreary middle of summer. I vividly recall one baking afternoon when something bizarre happened. Only a handful of us saw an odd van arrive and park in the open on the near-melting asphalt. It sat there strangely, until after a time a sliding door on the side panel slid open and tennis balls began to shoot out. First a few balls, and then a cascade, bounced about and tumbled everywhere. We were stupefied and more so when the mysterious van abruptly left – leaving us to chase and gather up the white, scruffy tennis balls. We later found out that a Calgary tennis club had donated its supply of used practice balls to the Home. For an afternoon, we threw them at the main roof, content to catch them on the bounce back until finally, tired of that, we tossed them all into the nearby canal. We happily watched the fuzzy flotilla drifting away.

That was the last of gaiety that summer, as the grim polio epidemic struck that year. We spent the balance of the summer under quarantine. They closed the iron gates, and affixed a big quarantine sign on them. I think that about eight or so of the children came down, all of whom were away for the summer. The rest of us spent weeks in utter boredom, having to take compulsory afternoon rest and could not even think about stealing away off the property. That too was the year that I came down with chickenpox and spent a week or so in the infirmary. The infirmary, on the main floor, served as a kind of two-bed isolation ward. Typically, the home relied on massive and regular doses of things like cascara and milk of magnesia to keep us healthy. We were isolated, but occasionally childhood illness erupted and the response was confinement. They fitted me out with fluffy large mittens (to thwart scratching) secured by a string that passed through my pajama sleeves and across the neck. That turned out to be one of the few occasions when my father sent me a gift to occupy myself in confinement. The gift was a cardboard punch-out and assemble model of the Titanic, with a multitude of tiny pieces to fit precisely together.

My memories would not be complete without mention of the home’s surroundings. That was forest, sweeping prairie and river. I remember the explosion of crocus bloom in spring, while winter still had claws locked in the ground. I could smell adventure, when rambling up on the expanses above the home site, on the wind, wafting from the front ranges of the mountains. That must explain why I have always felt a pull to the west – have loved mountains. There were hawks and owls, exciting to us, and though we imagined mountain lions and bears many of the things that attracted some of us were the riots of wild flowers on the edge of meadows, shadow and tremble of leaves, the smells of damp and decay in the darker patches. In early spring flowers burst out everywhere. We had, out back of us, rare groves of silent, giant old fir trees. One we named the Three Sisters. Daring always, we tied ropes to their muscular lower branches and swung, whooping, out over the plunging hillside. The forest and the trails were a safe place and something of my sanctuary. The river was my dream, the soaring of birds, my heart’s joy, and the distant peaks my siren call. All my life I have felt a love and appreciation for nature. That had its beginnings in the Woods Christian Home and it is one of the things that saved me, then and now.

Mr. T, the new boy’s supervisor, arrived that year too. He had served in the navy during the war. T was a muscular blonde man, who had an enthusiasm for sports and was something of an amateur artist. He could often be kind but had a volcanic temper. This became strikingly evident to me in an incident preceding the annual tour of the facility made by the board of directors. I had the assignment of boiler room cleaning. My work done, I waited by the door. A red-faced and impatient T showed up. Without a word, he reared up high and swiped a palm across the very top of the boiler. It came up dusty. Dropping down, he turned and seized the corn broom by the doorway. He then turned back and struck me, swinging full and hard with the bristle end across the face. I turned, stumbling and fell to my knees with my back to him. The blows kept coming, hard across my back and neck, while I cradled my head, fingers interlocked. All that time, he bellowed, “You are useless. Never amount to anything.”

This event did not change me much. It affected me, yes, but then I had been evolving into a mostly solitary boy. I could hardly bear it when we were not in school. Mr. Gaetz often allowed me to sprawl in the coatroom, reading whatever I wanted from the stacks of old National Geographic magazines. While bigger boys pursued reckless pursuits, like at night-time venturing boldly up on the laundry roof to reach some girls open windows, like staging spud fry feasts back in the woods and planning other escapades. I daydreamed about rockets and space exploration. I had become the Home’s book boy. Every few weeks, I would catch the bus into downtown Calgary, lugging a large canvas sack to bring back a supply of books for the small number of readers. I was first amongst them. I lost myself in books, Jules Verne and Joseph Conrad, every book on aeronautics and science I could grasp. Mr. Gaetz wrote on my report that I would one day become one of Canada’s great scientists or engineers. Getting old now, I sometimes think I would have better wasted my time on the typical boy’s more earthy and hormone driven interests. I was, of course, aware of girls but could not comprehend them at all; idealized them but had no idea how to attract them. Nor had I any idea of what I might do with those leggy, coltish dream girls.

One of my most vivid memories concerns a beauty who I will just call Prudence. She was an astonishingly beautiful girl – a sort of Norma Jean (young Marilyn Monroe) sort. She had a cascade of golden hair, more than budding breasts and stunning long legs. One day as we romped on the grass fronting the school, and you need understand that she was wearing a pale, summer cotton dress, we wrestled together, laughing. She got the upper hand and straddled me, pinning my arms, with those glorious legs astride me. Grinning wildly, her hair tumbling over my face, she challenged, “What are you going to do now Frankie.” I was, as you might imagine, science boy, completely flabbergasted. Thinking back now to that long-ago magical moment, I should have grinned and said, “I’m helpless darling, because I’ve just discovered that humans can melt.” I can see her still. Do I sometimes have regrets? Well sure, if for a summer I could have been a carefree, reckless, and happy boy! Truth is we had boys (and girls) like that in the Woods. They were glorious in their youth.

Looking back, I am most amused and still fascinated by the amazing and sometimes highly dangerous things that happened. I remember the times when on laundry duty, we put kids for dizzying rides in the dryers. Sure, we turned the heat off or at least low. We never did put a kid between the mangle rollers (that was the industrial machine used to iron sheets). I recall the boys finding a giant old truck tire. They then persuaded more easily influenced little kids to perch in the middle, clinging on with desperate hands. Set loose down the old, dry streambed, from high on the hillside. I can still see one of those tires, hurtling at great speed and bounding, spinning, five feet in the air as it crossed the driveway to ultimately crash on the front lawn. In winter, kids would loiter around the nearby bus stop to snatch onto the back bumper and as the bus careened off along the icy roads, they were sliding magnificently on the back. And some things were wonderfully dumb. We had two boys planning a runaway. They somehow seized on the idea of stealing a crate of frozen white fish (that was delivered every Friday), which they stashed up in the woods behind the school. (Don’t ask me how they intended to cook it, or carry it). Turns out that something came up to delay their planned getaway. The stink that emanated from their stash quashed all their plans.

With Mr. T’s arrival, sports became more important. He was keen on two things, team sports and the idea of transforming the Wood’s Home into something resembling Boys Town in Nebraska. He must have seen the famous old movie with the story about Father Flanagan. The film about it came out in thirty-eight. It had the memorable saying, “He ain’t heavy, Father, he’s my brother.” T drove all the way to Omaha, to film the campus with 8mm and learn about it. Never mind that we were not a Catholic institution and quite poor to boot. Likely, the founding concepts of Boy’s Town inspired him to create a family-like atmosphere and foster social skills. He tried. One thing he introduced was to have a gathering with cake for boy’s birthdays. He might even have baked the cake himself. He had a dark side though, possibly because of his wartime experiences and was a fierce disciplinarian. I can remember nighttime thumping, shouts and banging coming sometimes from his private bathroom after lights-out as he punished some lad.

We always had sports teams, but they were rag tag. I remember that our early basketball team had bathing trunks and hockey jerseys for uniforms. That started to change after we got a donation of used gymnastics equipment from the downtown YMCA. That is when my gymnasium terror began. I simply was not an athlete. My whole history had been as the last pick for ball teams. To this day, I cannot properly throw a ball overhand. I am physically incapable. No wonder I saw books as an alternative to an early interest in girls. I mean the girls in the home adored the sports stars. At the sight of a springboard my knees trembled. Vaulting over the box for me meant piling into it. The parallel bars had been created I am sure to dislocate both my shoulders. Then there was hockey.

In my very first game, Mr. T put me on defense. That was like appointing the kitchen staff to guard the castle gates against barbarian hordes. I could not skate backwards very well. I did so poorly on my first outing that it might have been someone on my own side, who put his stick blade hooked my blade and flipped me neatly onto my face. I knew instantly that my front tooth had been broken off clean at the gum line. I skated, bloodied to the bench, tears welling. T shouted at me, “Stop blubbering Dwyer. Get back in there.” So, he demoted me to goal tender, that being the only position with an incumbent more inept than I was, someone with near-opaque vision and creaky reflexes, someone terrified of the puck. I turned out to be brilliant in the role. It must have been the same hand speed and lightning reflexes, which had once transformed me, disastrously, into the boxing ring Canmore Kid. I remember that at the time the Calgary pro team had a spectacular goal tender with the unlikely first name of Eno – he was called Eno ‘the Cat’ Francis. I took to emulating Eno by artfully wrapping a white towel around my neck before games. I am sure though that the legendary Eno did not have, as I had, the sickening impulse to throw up before every game.

Mr. T was not through influencing me. What happened, this was over my last two years in the home (that would have been 1955-56) is that he began to exhibit a haphazard and alarming behavior. It always happened after meals and might have been five or six times in my recollection. We had to wait, without talking for twenty minutes, which time we occupied by singing hymns or reciting psalms. Mr. T sometimes pre-empted these ritualistic diversions. Something awful or some boy’s wrongdoing must have triggered him. He would storm in, red-faced and angry. Then he would berate us. Bellowing, “Your parents don’t love you. That is why you are here. Only the Woods Home loves you.” Then adding, “Most of your mothers are chippies (British slang meaning a prostitute or tramp of a woman). This verbal assault would go on for five minutes or more, as he glared at us, stalking around the front. He must have had a loose upper dental plate, because at the peak of his rant the plate would drop and protrude sideways, exuding froth and provoking smirks all round.

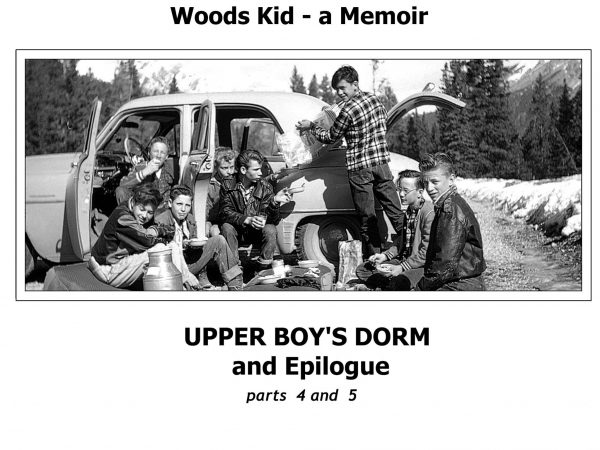

I became largely oblivious to events in my last year at the home. This was the year when momentous events happened. A new and strikingly young manager came in. He had a wife, a baby boy and a dog. That alone was amazing, but he had innovative ideas too. The winds of change were gusting through the place, but I could care less, did not notice. I was a short timer, a prince in an orphan house. When a youngster completed grade nine, he or she had to leave. So Art Jeal, the new manager called me into his office one April day to ask me if I wanted to be placed with a Calgary family or join my dad up in northern British Columbia. Of course, I wanted to be with my Pa. I had not seen him for a long time and I had no other family. I shaped my own fate. It would be years before I realized how momentous that decision was. A couple of months later – then fourteen years old – with prepaid bus and train tickets to Houston, B.C, eighty-two dollars in my billfold and a brand new duffel bag – I walked out through those old cast-iron gates, past the empty playground. Never looked back, as I strode out, so happy and optimistic. If I had, I would have seen that the Wood’s experience trailed behind me.

the end

EPILOGUE

Scooter – Scooter left the Home a few years after I departed. He had a tough time, and then it got worse. For a time, he lived in a car. He courted a lovely girl who told him, “If you change your ways, I will marry you.” He did, and she did. Scooter raised three sons and had a rewarding career with a great railroad. He died in 2016.

Cheeky – After some years in the Michener Centre – they sterilized him there – the authorities released him onto the streets of Calgary. He, according to an informed account, struggled. He took to hanging around racing tracks and associating with dubious types. My informant said that he viciously beat two men near to death with a tire iron. Cheeky was last known to have been somewhere in California. There is nothing else.

Mr. T – He died in 2005. His proudest achievement was to serve his country in the R.C.N. on the North Atlantic. His obituary describes him succinctly as a “great family man.” I visited Mr. T late in his life, and I have no doubt as to those distinctions. He was a contradiction.

Miss M – She is quoted in the quasi-official history of the Wood’s Christian Home, “Children of the Storm” as saying that “I loved working in the Home” and that, “I left because the (new) methods instituted by him (Mr. Jeal) were contrary to those which I was accustomed.”

Wood’s Christian Home – In the early sixties, the old Home underwent profound change. Cottages replaced the old dormitory model. There was a period of soul searching and a revaluation of the mission. 1966 brought about profound changes, with a new emphasis on child mental health and treatment models. In the early 1970s, the W.C.H. is described in Children of the Storm as “experiencing difficulties.” They tore the old mansion house down in 1975. For a time the doors were closed, only to see a re-emergence, and a new mission, as the Wood’s Homes in the 1980s. That entity has thrived. Today, it is highly regarded in Calgary and in Alberta.

Frankie Dwyer – I am one of the few left, now 84 years old. In 1956, the home offered me the choice of boarding with a kind family in Calgary or reuniting with my dad. After I left the Home, and while on my train journey to join my father, I stayed a night in a Prince George flophouse, only to be robbed of the eighty-six dollars I had to my name. What happened thereafter, over the next ten years or so, might prompt another novel. Just as a teaser, after a spell of homelessness, I wound up in a boarding house, cum boot-legging joint – splitting firewood for my keep in the winter – where the cast of vivid characters included Bonnie M. the proprietress, lodgers in various states of decrepitude and Bonnie’s adopted twins the myopic Buster and sparkly Bubbles.

Passing Innocence a novel. I submitted my writing to twenty-eight Canadian publishers and heard back from fourteen. One spelled my name wrong and only one encouraging. I have forgotten them all, except the exception. I still treasure it. Around 2001, I received a belated hand-written letter from an editor at the prestigious literary publisher, the House of Anansi. It was handwritten and post-marked New York City. The editor apologized for the long delay in considering my (full) manuscript. She said that, regrettably, the new owners had rejected my submission, even though the then Anansi editorial board had short-listed Passing Innocence to one of three Canadian Novels. That was the best rejection one could ever receive. It heartened me to, in part, create this website. I will always be grateful for that unknow editors kindness in writing to me. Francis Dwyer.

The mystery of the broken boy under the benches – Recently (that is November of 2022) I talked about this mystery (see the last paragraph of Little Boys End chapter) with a fellow old boy. He convinced me that the victim could not have been injured at a nearby golf course expansion, as the course had always been eighteen holes. I had earlier debunked the notion that the incident happened at clearing work for the Trans-Canada Highway (that construction took place a few years later). We concluded that this was the result of a beating in the big boy’s dorm basement. The story of having a log roll over him a fanciful inventions, intended to quell the curiosity of wide-eyed little kids. Having personally witnessed the whipping of a so-called faggot boy by a mob of big boys, I can believe this. There was rare, but appalling violence in the home I knew. Time has a way of burying truth and guilt is a great sealer of silence.

CONCLUSION

I will soon be eighty-five, bent a bit but not bowed. What I have learned to value most is kindness, courage, and humor. Levity is a great balm for tragedy, as is music. Accepting the dark side of my childhood home, those uplifting things were on constant display. I did not lack for brothers and sisters, many of them hugely admirable. It is true, we were glorious in our courage, our spirit and our epic escapades.